Scientists get the most realistic view yet of a coronavirus spike’s protein structure

The study, done on a mild-mannered relative of the virus that causes COVID-19, paves the way for seeing more clearly how spike proteins initiate infections, with an eye to preventing and treating them.

By Glennda Chui

Coronaviruses like the one that causes COVID-19 are studded with protein “spikes” that bind with receptors on the cells of their victims – the first step in infection. Now scientists have made the first detailed images of those spikes in their natural state, while still attached to the virus and without using chemical fixatives that might distort their shape.

They say their method, which combines cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and computation, should produce quicker and more realistic snapshots of the infection apparatus in various strains of coronavirus, a critical step in designing therapeutic drugs and vaccines.

“The advantage of doing it this way is that when you purify a spike protein and study it in isolation, you lose important biological context: How does it look in an intact virus particle? It could possibly have a different structure there,” said Wah Chiu, a professor at DOE’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University and senior author of the study. They described their results in Quarterly Reviews Biophysics Discovery.

Seven strains of coronaviruses are known to infect humans. Four cause relatively mild illnesses; the other three – including SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 – can be deadly, said co-author Jing Jin, an expert in the molecular biology of viruses at Vitalant Research Institute in San Francisco. Scientists at Vitalant hunt for viruses in blood and stool samples from humans and animals, screen blood samples during outbreaks like the current pandemic, and study interactions between viruses and their hosts.

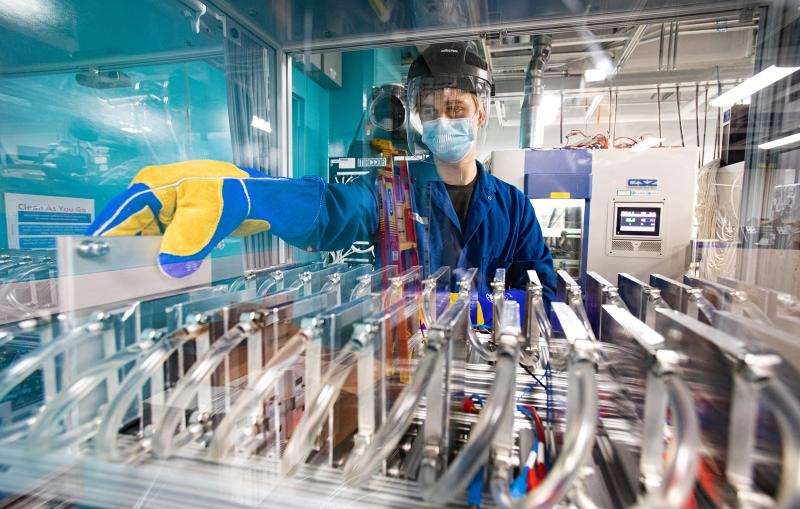

The virus that causes COVID-19 is so virulent that there are only a few cryo-EM labs in the world that can study it with a high enough level of biosafety controls, Jin said. So for this study, the research team looked at a much milder coronavirus strain called NL63, which causes common cold symptoms and is responsible for about 10% of human respiratory disease each year. It’s thought to attach to the same receptors on the surfaces of human cells as the COVID-19 virus does.

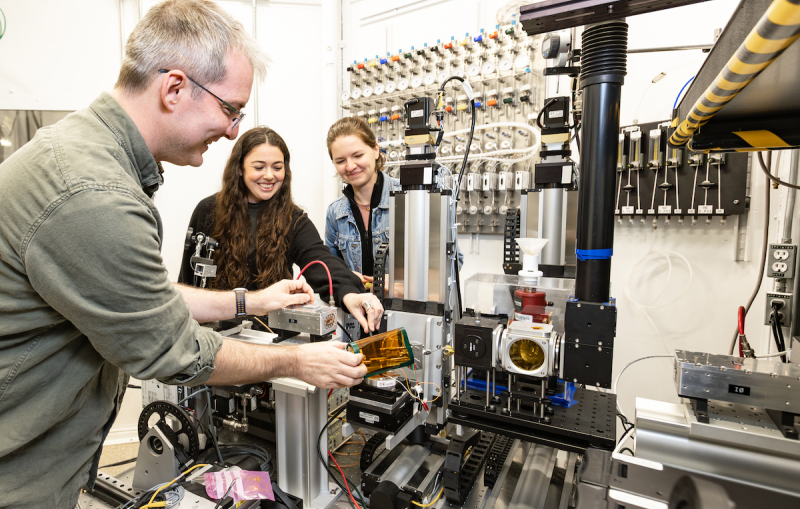

Rather than chemically removing and purifying NL63’s spike proteins, the researchers flash-froze whole, intact viruses into a glassy state that preserves the natural arrangement of their components. Then they made thousands of detailed images of randomly oriented viruses using cryo-EM instruments at the Stanford-SLAC Cryo-EM Facilities, digitally extracted the bits that contained spike proteins, and combined them to get high-resolution pictures.

“The structure we saw had exactly the same structure as it does on the virus surface, free of chemical artifacts,” Jin said. “This had not been done before.”

The team also identified places where sugar molecules attach to the spike protein in a process called glycosylation, which plays an important role in the virus’s life cycle and in its ability to evade the immune system. Their map included three glycosylation sites that had been predicted but never directly seen before.

Although a German group has used a similar method to digitally extract images of the spike protein from SARS-CoV-2, Jin said, they had to fix the virus in formaldehyde first so there would be no danger of it infecting anyone, and this treatment may cause chemical changes that interfere with seeing the true structure.

Going forward, she said, the team would like to find out how the part of the spike that binds to receptors on human cells is activated, and also use the same technique to study spike proteins from the virus that causes COVID-19, which would require specialized biohazard containment facilities.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act.

Citation: Kaiming Zhang et al., Quarterly Reviews Biophysics Discovery, 17 November 2020 (10.1017/qrd.2020.16)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.